Note to readers: I have added the label "Jamin Hubner"at the end of this and the other rejoinders in this series. If you click on the "Jamin Hubner" button, you can read all the rejoinders in this series.

This is the fourth part of a rejoinder to Jamin Hubner’s series of responses to my blog article,

“Three Basic Challenges to the ESV.”

The focus of this rejoinder is Hubner’s response to my third basic challenge to the ESV relating to the underlying original language texts from which it is translated.

Hubner begins by claiming he cannot understand why anyone would have concern with the modern critical Greek NT text as expressed in the NA 27th ed. and the UBS 4th ed. I will explain my concern in greater detail below.

Next, Hubner takes issue with my statement that the ESV abandons the traditional (received) text of Scripture as used by “the Protestant Reformers.”

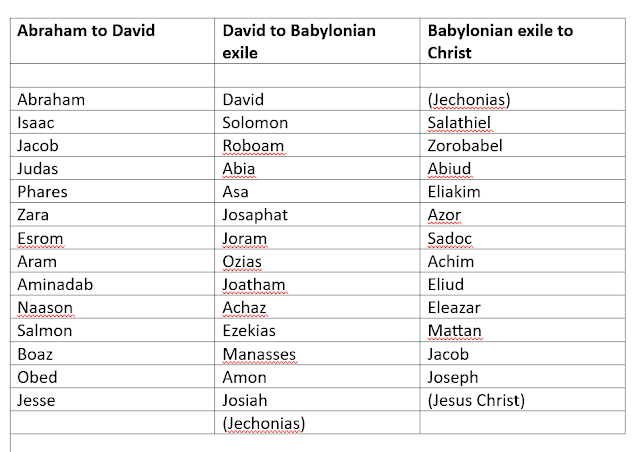

He asks, “Which ‘received text’ is Riddle referring to?” In answer, let me say that by “received text” I am referring to the original language texts of Scripture that have been most widely accepted and used by the church throughout its history. From a confessional perspective, we can speak of these texts being providentially preserved (see the Second London Baptist Confession of Faith, I.VIII which affirms that the Scriptures are “by his singular care and providence kept pure in all ages”). This includes the Masoretic text of the Hebrew Bible and the received text of the Greek New Testament, preserved in the vast majority of extant ancient manuscripts of the Bible. With the technological revolution of the printing press these texts were published and widely circulated for the first time during the Reformation era. In the NT, in particular, there were some slight modifications made in various editions of these printed editions, perhaps the most significant being the inclusion of the Comma Johanneum (1 John 5:7-8) in the third edition of Erasmus’ Greek NT (1522), but, all in all, the variations among the printed versions of the received text are minor. Printed editions of the received text provided a stable text as the basis for Protestant Bible translations, teaching, and preaching.

The Masoretic text of the Hebrew Bible can be found in modern editions of the Biblica Hebraica Stuttgartensia. The Trinitarian Bible Society also prints the Bomberg/Ginsberg edition of the Hebrew Bible (Masoretic text) first published by Daniel Bomberg in 1524-25 and edited by David Christian Ginsberg in 1894. As for the New Testament, the Trinitarian Bible Society publishes an edition of the received text that follows Beza’s 1598 Greek NT and was edited by F. H. A. Scrivener and published by Cambridge Press in 1894 and 1902. One can also consult Zane C. Hodges and Arthur Farstad, eds., The Greek New Testament According to the Majority Text, second ed. (Thomas Nelson, 1985) and Maurice Robinson and William G. Pierpont, eds. The New Testament in the Original Greek: Byzantine Textform 2005 (Chilton 2005).

It is an uncontroverted fact that the ESV is based on modern critical texts, not the traditional texts (the Masoretic Hebrew Text of the Old Testament and the received text of the New Testament) from which the translations of the Reformation era were made in the various “vulgar” European languages (German, English, French, Spanish, Italian, Hungarian, etc.). With regard to English, in particular, all of the Reformation era translations were based on the traditional, received original language texts. These include Coverdale’s Bible (1535); Matthew’s Bible (1537); the Great Bible (1539); the Geneva Bible (1560); Bishop’s Bible (1568); and the KJV (1611). The ESV, however, follows in the tradition of the English Revised Version (1881) and the RSV (1952) by departing from the Reformation era texts and basing its translation on the most current modern critical text, which significantly depart from the received text.

At this point let me offer an important aside on the general method of Hubner’s argument which I (and likely others) find confusing. As I stated in my first rejoinder, it is sometimes hard to know whether Hubner is responding to my article on the ESV, to

my review of Alan J. Macgregor’s book

Three Modern Versions, or directly to the arguments made in Macgregor’s

Three Modern Versions (which I believe he has encountered primarily in extended quotes in my article and review and not by reading Macgregor directly). Confusion comes when Hubner presents his posts as responses to my ESV article, but then he attacks positions and arguments I did not advocate in that article, but which he assumes I (or Macgregor) hold or make relating to the KJV. This confusion is particularly evident in Hubner’s part four response.

Here is an example. In my ESV article I state that, “the ESV is not based on the traditional texts of Scripture that were used by the Protestant Reformers in their vernacular translations….” Note: I am discussing the ESV. Hubner quotes this passage and responds: “and how is it that this text is used ‘by the Protestant Reformers,’ since neither Luther, Calvin, or Zwingli lived when it came into existence around 1611?” Hubner is discussing the KJV. Furthermore, he apparently mistakenly believes that the received text did not come into existence until the KJV translation. The traditional text, however, was around long before the KJV (Erasmus’ first edition of the Greek NT came out in 1516 and Bomberg’s Hebrew Bible in 1524-25, some 75-100 years before the KJV; see the list above of English Bibles prior to the KJV that relied on the traditional text). This point is even conceded by James White in the quote that Hubner cites to refute my position (!): “Everyone admits that the Greek text utilized by Luther in his preaching and by Calvin in his writings was what would become known as the TR.” My concern is that the ESV is not based on this text. It has followed in the path of translations that have abandoned this text in favor of the modern critical text.

Next, Hubner cites the examples I offered of places where the ESV’s divergence from the traditional text might be observed. Again, my article was very brief (just c. 1,600 words) and the four examples (Psalm 145:13; Mark 16:9-20; John 7:53-8:11; Acts 8:37) were meant to be illustrative and not exhaustive. Many, many more might be offered (a more extensive list of differences between the traditional text of the NT and the modern critical text can be found in the Trinitarian Bible Society tract “A Textual Key to the NT”).

Hubner begins by saying, “Clearly, the ESV engages in textual criticism. But, wouldn't we hope so?” My stated concern here, however, is with the text used by the ESV, not the discipline of textual study per se (though I have some thoughts on that subject too, as you might imagine).

Hubner next shares several presuppositions with which I would differ:

First, he assumes that the last 400 years have seen “the greatest discoveries of NT manuscripts” (presumably Codex Sinaiticus and various papyri) and that these justify the usurpation of the traditional text by the modern critical text. I believe that Hubner vastly overestimates the significance of these finds and underestimates the degree to which faithful reformation era scholars were familiar with nearly all the textual issues under discussion in our day. As E. F. Hills observed: “Indeed almost all the important variant readings known to scholars today were already known to Erasmus more than 460 years ago and discussed in the notes (previously prepared) which he placed after the text in his editions of the Greek New Testament” (The King James Version Defended, pp. 198-199). The Reformers knew about pertinent textual issues like the pericope adulterae and the ending of Mark, but they chose to follow the traditional text. One might also compare here Harry Sturz’s book The Byzantine Text-Type (Thomas Nelson, 1984) in which he examines the modern papyri finds and finds support for the traditional (Byzantine) text.

Second, Hubner assumes that no reasonable person could possibly believe that the pericopae adulterae (John 7:53-8:11) is part of the text of Scripture. He asks, “And, is Riddle really suggesting the pericope in John 7:53-8:11 was in the original?” My scandalous answer is, “Yes, I am suggesting this.” Calvin agreed when he stated in his commentary on this passage that “as it has always been received by the Latin Churches, and is found in many old Greek manuscripts, and contains nothing unworthy of an Apostolic Spirit, there is no reason why we should not apply it to our advantage.” Hubner adds, “It would be interesting to see the textual reasons for this conclusion, given that it isn't found in any the earliest manuscripts (2nd-4th century), or any of the 4th century codices, or in most of the early church fathers, etc.” The marginal note on John 7:53 in the NKJV states that the modern critical text “brackets 7:53 through 8:11 as not in the original text. They are present in over 900 mss of John.” For one cogent defense of the integrity of this passage in the NT, see Hills’ discussion, including his review of references to this passage in Ambrose, Augustine, Jerome, the Didascalia (Teaching) of the Apostles, the Apostolic Constitutions, Eusebius, and Pacian (pp. 150-159).

Next, Hubner raises four questions or statements:

“First of all, what does Riddle mean by ‘traditional text’?” For an answer, see my response above.

“Second, why does a departure from this ‘traditional text’ ought to raise considerable alarm?” (sic; I take him to be asking, “Why should a departure from this ‘traditional text’ raise considerable alarm?”). He claims I gave no reasons for this alarm and ends with a confusing accusation that I have offered this critique of the ESV “in an effort to uphold the superiority of one 400 year old Anglican translation.” Once again, my article addresses the ESV not the KJV. My argument is about the ESV’s departure from the traditional text of Scripture not from the KJV translation. To make matters worse, he then clearly attempts to disparage the KJV by misidentifying it as a “400 year old Anglican tradition.” First, the traditional text predates the KJV translation. Second, though its origin was in the Protestant Church of England, it became the Bible of choice in the English speaking world among men of all denominational and confessional perspectives (including those who could hardly be accused of being “Anglican,” from Bunyan to Spurgeon to Lloyd-Jones).

“Third, this entire paragraph [cited from my ESV article] is a bad argument.” Again, the whole ESV/KJV confusion arises, but we will proceed. Hubner here claims that those who oppose new translations based on the modern critical text (like the ESV) would also have opposed the KJV translation of 1611. He misses this key point: The KJV was a new translation, but it was not done on the basis of a new text! The KJV was based on the same text used to translate the Geneva Bible and all the other Reformation era English translations! The concern I raise in my article is not with new translations but with new texts! Am I worried about what new editions of the modern critical text might do with the Bible? Yes, I am. More on this in point four below.

Finally, Hubner asks, “Fourth, what is meant by ‘the secular academy,’ and is not this association argument just as invalid as the first regarding the copyright-holder of the ESV?” Let me be clearer than I could in my brief article. By “the secular academy” I mean those who teach in religion departments in public and private universities, who associate in professional academic societies (like the AAR and SBL), who influence liberal Bible societies across the world, and who are not confessional Christians and members of Biblical local churches. The text of the Bible has been taken out of the hands of the church and placed into the hands of the academy (and Bible Societies and publishers). I think it should gravely concern the church, for example, that Ehrman has taken over editorial work on Metzger’s influential The Text of the New Testament. Will he chair a new revision of the UBS Greek NT? Will he write or edit the next Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament? What about the Deutche Bibelgesellschaft which will produce the next edition of Nestle-Aland? Are Reformed and evangelical believers really going to look to liberal mainline European Protestant and, now, even Roman Catholic scholars in Germany to define for us the text of Scripture? If you submit to the modern critical text, this is, in effect, what you are doing.

Ronald Reagan once said that the most terrifying words in the English language are, “I’m from the government, and I’m here to help.” I think we could paraphrase that and say the most terrifying words for the faithful church would be, “I’m from the academy, and I’m here to help.” Or especially, “I’m from the academy, and I’m here to fix your text of Scripture.”

After the four questions or statements above, Hubner cites another paragraph in my article in which I raise a specific danger about relying on modern critical texts. Namely, the result is guaranteed textual instability. Again, even though my point in the citation is about the text of the ESV (and I never even mention the KJV!), Hubner launches into another attack relating to the KJV, projecting arguments upon me again that I did not make in this article. His comments here once again also reflect misunderstanding about the fact that the KJV was a new translation, but it did not offer a new text. My point in challenge three is that the ESV is based on a new text.

He concludes this section by asking, “In sum, on what grounds does Riddle assert the KJV AV 1611 as the ultimate reference point in evaluating all other translations and editions of the NT?” I hate to be redundant, but to cite Reagan once more, I would have to say to Mr. Hubner, “There you go again.” We might well have a discussion on why one might choose the KJV as “the ultimate reference point” for English translations based on the merits of its text, translation, history, etc. (as Macgregor does in Three Modern Versions), but that is not the point I am making in this article. My article is about the ESV not the KJV.

Hubner next throws out a specific reference to the text and translation of Revelation 16:5 in the KJV and NKJV. Again, this would make for an interesting discussion, and I believe there is, without doubt, a more credible case that can be made for the KJV/NKJV rendering of this verse than Hubner is aware, but, in the end, it is not germane to our discussion of the ESV. I might also add here that in my ESV article I cited the ESV’s decision to depart from the Masoretic text of Psalm 145:13 by adding a line supported by only one Hebrew manuscript. In his zeal to discuss the KJV, Hubner seems to have ignored the focus of my article, the ESV, including my specific reference to Psalm 145:13. Along these lines, I might cite similar issues in the ESV. The RSV/ESV rendering of 1 Samuel 7:19, for example, provides a reading (“seventy men”) that is not supported by any Hebrew manuscript (the MT here reads “seventy men, fifty thousand” and translations based on the traditional text typically render it as “fifty thousand and seventy men” (NKJV; cf. Geneva Bible, KJV; note: the NASB also reads, “50, 070”; see my posts on the text and translation of 1 Samuel 6:19:

part one;

part two;

part three).

More KJV refutation comes when Hubner states that I am operating under two assumptions: “(1) we cannot improve upon the AV 1611, (2) we should not attempt to improve upon the AV 1611 (lest we be ‘unstable’). Both are false.” Again, Hubner foists these assumptions regarding the KJV upon me rather than addressing my stated concerns about the text of the ESV. Note that he confuses my point on instability as relating to the KJV translation and not to the text of Scripture.

He refutes the first supposed “assumption” by citing White’s “definitive work on the subject.” I guess the KJV can be improved upon but not White’s “definitive”

The KJV Only Controversy! Clearly, not all see White’s work as “definitive” (for one critique, see, e.g., Theodore Letis’s review of White’s book in

The Ecclesiastical Text, pp. 222-229). In truth, White’s work is either ignored or dismissed as irrelevant in the secular text critical academic guild. Evangelical text critics like Daniel Wallace (see my critique of Wallace here:

part one;

part two;

part three;

part four;

part five) and popular apologists like White are defending a vision of text criticism (the search for the original autographic text) that has been abandoned by the postmodern academy which now no longer searches for a fixed autograph but sees the “texts” (plural!) as a “moving stream” (J. N. Birdsall) or a “living text” (see David Parker,

Living Texts of the Gospels [Cambridge, 1997]). The definitive current textbook on academic textual criticism, David Parker’s

An Introduction to Manuscripts and Their Texts [NB: the plural] (Cambridge, 2008), does not include a single reference to Wallace or White in its index.

Hubner refutes the second supposed “assumption” by saying that the “clear attitude” of “any Christian” should be that we wish to “improve” both the text and translation of the Bible. The very modern idea that we need to “improve” the text of Scripture is, however, the very notion I would wish to challenge. Hubner begs the question.

Hubner concludes:

"As it has been demonstrated in this blog series, all three of the "challenges" of the ESV are based on bad arguments, half-truths, and the lack of facts. None of them stand. As such, the ESV should not be placed beneath the AV 1611 in terms of importance, accuracy, and edification for the church, nor should the ESV be dismissed in general as a liberal or untrustworthy translation - anymore than should the KJV."

I will leave it to the readers of this interchange to determine if my brief blog article “Three Basic Challenges to the ESV” is, in fact, “based on bad arguments, half-truth, and lack of facts.” I believe that the three challenges I originally articulated concerning the ESV remain unshaken:

1. The ESV has a National Council of Churches copyright.

2. The ESV is not, in fact, a new translation but an evangelical revision of a notoriously liberal one.

3. The ESV is based on the modern critical Greek text.

I believe that all three of these challenges should be seriously considered by believers and churches as they evaluate whether to make use of the ESV at the pulpit, lectern, or pew.

JTR