Stylos is the blog of Jeff Riddle, a Reformed Baptist Pastor in North Garden, Virginia. The title "Stylos" is the Greek word for pillar. In 1 Timothy 3:15 Paul urges his readers to consider "how thou oughtest to behave thyself in the house of God, which is the church of the living God, the pillar (stylos) and ground of the truth." Image (left side): Decorative urn with title for the book of Acts in Codex Alexandrinus.

Tuesday, August 15, 2023

Tuesday, June 20, 2023

Augustine, Harmony of the Evangelists.2.12: Concerning the words ascribed to John the Baptist

Notes:

In this episode, we are looking at Book 2, chapter 12 where Augustine addresses issues related to the veracity of the Gospel records in reporting the recorded speech of John the Baptist.

2.12: Concerning the words ascribed to John by all four of

the evangelists respectively.

Augustine here investigates how the reader might understand

statements attributed to John the Baptist in each Gospel respectively, while

harmonizing such statements overall as they appear throughout all four Gospels.

How does one, in particular, understand statements attributed to John that seem

to differ from one account to another? This discussion might be described as

addressing the question of whether the evangelists reported the ipsissima

verba (the very words), in this case of John the Baptist, or the ipsissima

vox (the very voice, but not the exact words).

Augustine begins with a discussion of how one differentiates

and recognizes direct quotation of speech. How does one distinguish between

something Matthew says and something John says when the text does not use some

clear grammatical indicator of direct quotations. He gives as an example the

statement in Matthew 3:1-3, which begins, “1 In those days came John the

Baptist, preaching in the wilderness of Judea, 2 And saying, Repent ye: for the kingdom of

heaven is at hand.” The question is whether or not the next statement in v. 3 [

“For this is he that was spoken of by the prophet Esaias, saying, The voice of

one crying in the wilderness, Prepare ye the way of the Lord, make his paths

straight.”] was also spoken by John or information added by Matthew. In other

words, where does the quotation from John end? At v. 2 or at v. 3? Augustine

notes that Matthew and John sometimes speak of themselves in the third person

(citing Matthew 9:9 and John 21:24), so v. 3 might legitimately have been

spoken by John the Baptist. If so, it harmonizes with John’s statement in John

1:23, “I am the voice of one crying in the wilderness.”

Such questions, according to Augustine, should not “be deemed

worth while in creating any difficulties” for the reader. He adds, “For

although one writer may retain a certain order in the words, and another

present a different one, there is really no contradiction in that.” He further

affirms that word of God “abides eternal and unchangeable above all that is

created.”

Another challenge comes with respect to the question as to whether

the reported speech of persons like John are given “with the most literal

accuracy.” Augustine suggests that the Christian reader does not have liberty

to suppose that an evangelist has stated anything that is false either in the

words or facts that he reports.

He offers an example Matthew’s record that John the Baptist

said of Christ “whose shoes I am not worthy to bear” (Matthew 3:11) and Mark’s

statement, “whose shoes I am not worthy to stoop down and unloose” (Mark 1:7;

cf. Luke 3:16). Augustine suggests that such apparent difficulties can be

harmonized if one considers that perhaps each version gets the fact straight

since “John did give utterance to both these sentences either on two different

occasions or in one and the same connection.” Another possibility is that “one

of the evangelists may have reproduced the one portion of the saying, and the

rest of them the other.” In the end the most important matter is not the variety

of words used by each evangelist but the truth of the facts.

Conclusion:

According to

Augustine, when it comes to addressing “the concord of the evangelists” one

finds “there is not divergence [to be supposed] from the truth.” Thus, he contends

that any apparent discrepancies or contradictions can be reasonably explained.

For Augustine variety of expression does not mean contradiction.

JTR

Tuesday, June 13, 2023

Tuesday, May 09, 2023

Augustine, Harmony of the Evangelists.2.3-4: Genealogies

This is a series of readings from and notes and commentary upon

Augustine of Hippo’s Harmony of the Evangelists.

In this episode we are looking at Book 2, chapter 3-4 where

Augustine addresses both supposed conflicts between and among the genealogies

of Matthew 1 and Luke 3.

2.3: A statement of the reason why Matthew enumerates one

succession of ancestors for Christ, and Luke another.

Augustine begins by noting in particular a difference between

Matthew and Luke in the line between David and Joseph in the two genealogies. They

follow different directions with Matthew offering a series “beginning with

David and traveling downwards to Joseph,” and Luke, on the other hand, having “a

different succession, ”tracing it from Joseph upwards….” The main source of the

difference, however, is in the order between Joseph and David and the fact that

Joseph is listed as having two different fathers. Augustine explains that one

of these was Joseph’s natural father by whom he was physically begotten (Jacob,

in Matthew), and the other was his adopted father (Heli, in Luke). Both of

these lines led to David.

Augustine further notes that adoption was an ancient custom. Though

terms like “to beget” generally indicate natural fatherhood, Augustine notes

that natural terms can also be used metaphorically, so Christians can speak of

being begotten by God (e.g., cf. John 1:12-13: “to them he gave power to become

the sons of God”). Augustine thus concludes, “It would be no departure from the

truth, therefore, even had Luke said that Joseph was begotten by the person by

whom he was really adopted.” Nevertheless, he sees significance in the fact

that Matthew says “Jacob begat Joseph” (Matthew 1:16; indicating he was the

natural father) and Luke says, “Joseph, which was the son of Heli” (Luke 3:23;

indicating he was the adopted father of Joseph). Those unwilling to seek

harmonizing explanations of such texts “prefer contention to consideration.”

2.4: Of the reason why forty generations (not including

Christ Himself) are found in Matthew, although he divides them into three

successions of fourteen each.

Augustine begins by noting that consideration of this matter

requires a reader “of the greatest attention and carefulness.” Matthew who

stresses the kingly character of Christ lists forty names in his genealogy. The

number forty is of obvious spiritual significance in the Bible. Moses and

Elijah each fasted for forty days, as did Christ himself in his temptation. After

his resurrection, Christ also appeared to his disciples for forty days. He sees

numerological significance in the fact that forty is four time ten. There are

four directions (North, South, East, and West) and ten is the sum of the first

four numbers.

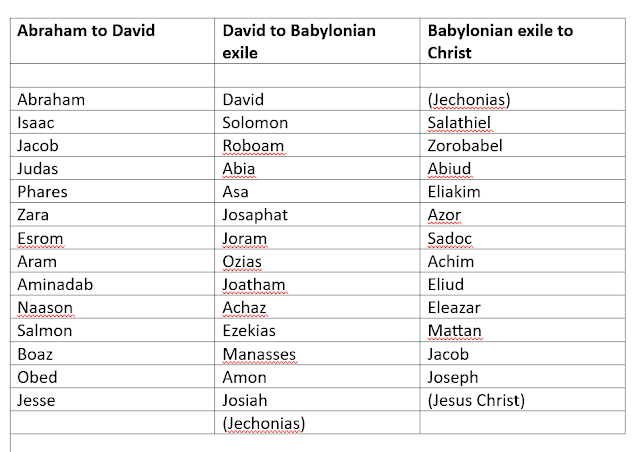

Matthew intentionally desires to list forty generations, but

he also suggests three successive eras (Abraham to David; David to Babylonian

exile; Babylonian exile to Christ). This would be fourteen generations each for

a total of forty-two, but Matthew, Augustine suggests, offers a double

enumeration of Jechonias, making it “a kind of corner” and excluding it from

the overall count, resulting then in the more spiritually significant number

forty.

Augustine suggests that Matthew’s genealogy stresses Christ

taking our sins upon himself, while Luke, who focuses on Christ as a Priest, stresses

“the abolition of our sins.” He sees significance in Matthew’s line from David

through Solomon by Bathsheba, acknowledging David’s sin, while Luke’s line

flows from David through Nathan, whom Augustine erroneously ties to the prophet

Nathan, by whose confrontation with David, God took away sin.

He also sees numerological significance in the fact that Luke’s

genealogy includes seventy-seven persons (counting Christ and God himself). He

sees the number seventy-seven as referring to “the purging of all sin.” Eleven

breaks the perfect number ten, and it was the number of curtains of haircloth

in the temple (Exodus 26:7). Seven is the number of days in the week. Seventy-seven

is the product of eleven times seven, and so it is “the sign of sin in its

totality.”

Conclusion:

The harmonization

of the genealogies has been a perennial issue in Gospel studies from the

earliest days of Christianity (see Eusebius’ citation of Africanus in his EH).

Augustine maintains the continuity and unity of both Gospel genealogies while

also noting the uniqueness of each individual Gospel account. In both

genealogies Augustine offers pre-critical insight into the intentional use of spiritually

significant numbers (forty in Matthew; seventy-seven in Luke) to heighten what

he sees as the theological perspectives and intentions of the Evangelists.

JTR

Addendum:

Here's a chart showing Augustine's breakdown of the genealogy in Matt 1:1-17 which yields 40 names according to his calculation. He excludes in his scheme Jechonias as "a kind of corner" and Jesus Christ as "the kingly president" over the whole.

Friday, February 10, 2023

Tuesday, January 24, 2023

Byzantine Colophons Suggesting Dates for the Four Canonical Gospels

Note: Taken from twitter: @Riddle1689:

Dating the Gospels is a longstanding challenge in NT studies.

Friday, July 16, 2021

Introduction: Augustine, Harmony of the Evangelists

Notes:

Introduction to this Project

I am undertaking a consecutive reading along with notes and

commentary of Augustine of Hippo’s work Harmony of the Evangelists [De

Consensu Evangelistarum], also known under the title The Harmony of the

Gospels.

For the reading, I am going to be making use of this English

translation edition:

From Marcus Dodds, Ed., The Works of Aurelius Augustine,

Bishop of Hippo. A New Translation. Vol. VIII. The Sermon on the Mount,

and the Harmony of the Evangelists. Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1873.

Translated by S. F. D. Salmond.

For the work in Latin online, look here.

A Very Brief Sketch of the Life of Augustine of Hippo

Augustine (354-430) was the influential bishop of Hippo in

North Africa. He was born to a Christian mother, Monica, and a pagan father. He

was intellectually gifted, embraced Neoplatonic philosophy, and became a

teacher of rhetoric in Milan, Italy. In Italy he dabbled in an Eastern religion

known as Manichaeism, which he rejected, and eventually came under the sway of

the preaching of Ambrose, the bishop of Milan. In 386 he was converted while

walking in a garden, having heard a voice say Tolle lege (“Take up and

read.”), having picked up a Bible to read Romans 13:13.

After his baptism he returned to North Africa thinking he

might establish a monastic community with a circle of his Christian friends,

but he was soon pressed into ministerial service by his local bishop and

eventually become bishop himself of Hippo. Augustine was a prolific writer,

teacher, and theologian. He was also a polemicist and apologist engaged in the great

controversies of his day, including the Donatist Controversy dealing with the

restoration of those who had accepted compromise during earlier seasons of persecution

and the Pelagian Controversy, dealing with the unorthodox teaching of Pelagius,

who denied the power and extent of sin among fallen men.

Among Augustine’s two best known works are his Confessions,

which many consider to be the earliest example of an autobiography, and The

City of God, his defense of Christianity in the face of those pagans who

blamed Christianity for the fall of Rome (AD 410). When he died, his own city

of Hippo was besieged.

Augustine’s writings had an immense influence in the generations

after his death, particularly in the Western world. In the Middle Ages he was

acknowledged to be one of the four preeminent “Doctors” of the Western church

(the others being Gregory the Great, Ambrose, and Jerome). His teachings on original sin,

predestination, and the sovereignty of God in salvation were among the

hallmarks of what would come to be called “Augustinian” theology, a perspective

that was heartily retrieved, in particular, at the time of the Protestant

Reformation.

A Brief Introduction to the Harmony

This introduction is based on S. F. D. Salmond’s

“Introductory Notice” provided in the 1873 edition (135-138).

The composition of the work is assigned to about the year AD

400. According to Salmond, “Among Augustine’s numerous theological productions,

this one takes rank with the most toilsome and exhaustive” (135-136). It is an

apologetic and polemical work. The editor notes, “Its great object is to

vindicate the Gospel against the critical assaults of the heathen” (136).

Persecution having failed, pagans tried to discredit the faith “by slandering

its doctrine, impeaching its history, and attacking with special persistency

the veracity of the gospel writers” (136). He continues, “Many alleged that the

original Gospels had received considerable additions of a spurious character.

And it was a favorite manner of argumentation, adopted by both pagan and

Manichean adversaries, to urge that the evangelical historians contradicted

each other” (136).

The plan of the work is presented in four divisions:

In Book 1, “he refutes those who asserted that Christ was

only the wisest among men, and who aimed at detracting from the authority of

the Gospels, by insisting on the absence of any written compositions proceeding

from the hand of Christ Himself, and by affirming that the disciples went

beyond what had been His own teaching both on the subject of His divinity, and

on the duty of abandoning the worship of the gods” (136).

In Book 2, “he enters upon a careful examination of Matthew’s

Gospel, on to the record of the supper, comparing it with Mark, Luke, and John,

and exhibiting the perfect harmony subsisting between them” (136-137).

In Book 3, Augustine “demonstrates the same consistency

between the four evangelists, from the account of the supper to the end” (137).

In Book 4, “he subjects to a similar investigation those

passages in Mark, Luke, and John, which have no proper parallels in Matthew”

(137).

Salmond notes that in taking up this task Augustine was both “gifted

with much, but he also lacked much.” He had a high view of Scripture, but “he

was deficient in exact scholarship” (137). Though well versed in Latin

literature, “he knew little Greek, and no Hebrew” (137). The editor notes that

there is “less digression” than is customary in his writing, and he less

frequently indulges in “extravagant allegorizing” (137). He has “an inordinate

dependence” on the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible) and

almost seems to claim “special inspiration” for it (137-138).

With respect to Augustine’s harmonization of the Gospel

narratives, Salmond observe: “In general, he surmounts the difficulty of what

may seem at first sight discordant versions of one incident, by supposing

different instances of the same circumstances, or repeated utterance of the

same words” (138). Furthermore, “He holds emphatically by the position that

wherever it is possible to believe two similar incidents to have taken place,

no contradiction can legitimately be alleged, although no evangelist may relate

them both together” (238).

Finally, Salmond suggests Augustine’s work should not be

subjected to overly harsh judgement given he entered “an untrodden field”

(138). His work cannot be denied “the merit of grandeur in original conception,

and exemplary faithfulness in actual execution” (138).

It is this Harmony

that we will attempt to read and offer notes and commentary in upcoming

episodes in this series.

JTR

Monday, June 14, 2021

Wednesday, June 09, 2021

Tuesday, June 08, 2021

Clement of Alexandria: Who is the Rich Man That Shall Be Saved? (Part 2 of 8)

Thursday, May 27, 2021

Gospels Class Upcoming at IRBS Seminary August 3-7, 2021

Tuesday, May 25, 2021

Book Review: Metropolitan Hilarion Alfeyev, The Life and Teaching of Jesus, Vol. 1:The Beginning of the Gospel

Saturday, May 08, 2021

WM 203: Warfield: Why Four Gospels?

Monday, March 01, 2021

Book Review: Peter J. Williams, Can We Trust the Gospels?

Tuesday, February 04, 2020

Q & A on John the Baptist, Jesus, and the Gospels

Tuesday, September 03, 2019

Ned B. Stonehouse on the Authorship and Anonymity of the Canonical Gospels

Thursday, May 30, 2019

Peter J. Williams on why the "telephone game" analogy is ill chosen for the transmission of Jesus traditions in the NT Gospels

In the book Williams provides reasonable arguments as to why the information about Jesus in the NT Gospels should be considered historically reliable.