Stylos is the blog of Jeff Riddle, a Reformed Baptist Pastor in North Garden, Virginia. The title "Stylos" is the Greek word for pillar. In 1 Timothy 3:15 Paul urges his readers to consider "how thou oughtest to behave thyself in the house of God, which is the church of the living God, the pillar (stylos) and ground of the truth." Image (left side): Decorative urn with title for the book of Acts in Codex Alexandrinus.

Monday, September 02, 2024

Tuesday, June 20, 2023

Augustine, Harmony of the Evangelists.2.12: Concerning the words ascribed to John the Baptist

Notes:

In this episode, we are looking at Book 2, chapter 12 where Augustine addresses issues related to the veracity of the Gospel records in reporting the recorded speech of John the Baptist.

2.12: Concerning the words ascribed to John by all four of

the evangelists respectively.

Augustine here investigates how the reader might understand

statements attributed to John the Baptist in each Gospel respectively, while

harmonizing such statements overall as they appear throughout all four Gospels.

How does one, in particular, understand statements attributed to John that seem

to differ from one account to another? This discussion might be described as

addressing the question of whether the evangelists reported the ipsissima

verba (the very words), in this case of John the Baptist, or the ipsissima

vox (the very voice, but not the exact words).

Augustine begins with a discussion of how one differentiates

and recognizes direct quotation of speech. How does one distinguish between

something Matthew says and something John says when the text does not use some

clear grammatical indicator of direct quotations. He gives as an example the

statement in Matthew 3:1-3, which begins, “1 In those days came John the

Baptist, preaching in the wilderness of Judea, 2 And saying, Repent ye: for the kingdom of

heaven is at hand.” The question is whether or not the next statement in v. 3 [

“For this is he that was spoken of by the prophet Esaias, saying, The voice of

one crying in the wilderness, Prepare ye the way of the Lord, make his paths

straight.”] was also spoken by John or information added by Matthew. In other

words, where does the quotation from John end? At v. 2 or at v. 3? Augustine

notes that Matthew and John sometimes speak of themselves in the third person

(citing Matthew 9:9 and John 21:24), so v. 3 might legitimately have been

spoken by John the Baptist. If so, it harmonizes with John’s statement in John

1:23, “I am the voice of one crying in the wilderness.”

Such questions, according to Augustine, should not “be deemed

worth while in creating any difficulties” for the reader. He adds, “For

although one writer may retain a certain order in the words, and another

present a different one, there is really no contradiction in that.” He further

affirms that word of God “abides eternal and unchangeable above all that is

created.”

Another challenge comes with respect to the question as to whether

the reported speech of persons like John are given “with the most literal

accuracy.” Augustine suggests that the Christian reader does not have liberty

to suppose that an evangelist has stated anything that is false either in the

words or facts that he reports.

He offers an example Matthew’s record that John the Baptist

said of Christ “whose shoes I am not worthy to bear” (Matthew 3:11) and Mark’s

statement, “whose shoes I am not worthy to stoop down and unloose” (Mark 1:7;

cf. Luke 3:16). Augustine suggests that such apparent difficulties can be

harmonized if one considers that perhaps each version gets the fact straight

since “John did give utterance to both these sentences either on two different

occasions or in one and the same connection.” Another possibility is that “one

of the evangelists may have reproduced the one portion of the saying, and the

rest of them the other.” In the end the most important matter is not the variety

of words used by each evangelist but the truth of the facts.

Conclusion:

According to

Augustine, when it comes to addressing “the concord of the evangelists” one

finds “there is not divergence [to be supposed] from the truth.” Thus, he contends

that any apparent discrepancies or contradictions can be reasonably explained.

For Augustine variety of expression does not mean contradiction.

JTR

Tuesday, June 06, 2023

Augustine, Harmony of the Evangelists.2.9-11: Harmonizing the Infancy Narratives

Notes:

In this episode, we are looking at Book 2, chapter 9-11where

Augustine addresses several points where some readers might see apparent

contradictions in the infancy narratives of Matthew and Luke.

2.9: An explanation of the circumstance that Matthew states

that Joseph’s reason for going into Galilee with the child Christ was his fear

of Archelaus, who was reigning at that time in Jerusalem in place of his

father, while Luke tells us that the reason for his going into Galilee was the

fact that their city Nazareth was there.

This brief chapter continues the discussion concerning

Archelaus which began in 2.8. Augustine harmonizes Matthew’s account of Joseph’s

fear of going into Judea given the reign of Archelaus, the angelic warning, and

the decision to go into Galilee (Matthew 2:22) with Luke’s account noting that Mary

and Joseph were originally from Nazareth of Galilee. He suggests that if there had not been fear of

Archelaus, they might instead have settled in Jerusalem, where the temple was.

2.10: A statement of the reason why Luke tells us that His

parents went to Jerusalem every year at the feast of the Passover along with

the boy; while Matthew intimates that their dread of Archelaus made them afraid

to go there on their return from Egypt.

Augustine must have known of some critics who saw the mention

of Archelaus in Matthew as somehow being at odds with Luke’s account on various

levels including the mention of the family’s frequent trips to Jerusalem.

Augustine notes that none of the Evangelists reveal how long Archelaus reigned.

Thus, he might have had only a short

reign. If it was longer, the family might have gone up stealthily, without

drawing notice to themselves. If this were the case, it only magnifies their

piety and faithfulness, despite these threats. Objections to the harmony of

Matthew and Luke are not insuperable.

2.11: An examination of the question as to how it was

possible for them to go up, according to Luke’s statement, with Him to

Jerusalem to the temple, when the days of the purification of the mother of

Christ were accomplished, in order to perform the usual rites, if it is

correctly recorded by Matthew, that Herod had already learned from the wise men

that the child was born in whose stead, when he sought for Him, he slew so many

children.

Augustine here tackles another perceived difficulty. How did

the family of Jesus go to the temple in Jerusalem for purification if Herod was

threatening his life? Augustine offers several explanations. One is that Herod

would have been too busy with other royal affairs to notice their visit.

Another is that he might not yet have been aware of the escape of the wise men.

Only after this purification rite was done and they escaped to Egypt did it

enter Herod’s mind to slay the innocents. Augustine even suggests Herod might

have been prompted to perform this evil act after hearing the publicity

relating to the words spoken by Simeon and Anna at the infant Christ’s visit to

Jerusalem.

Conclusion:

In these three short chapters Augustine suggests various reasonable

explanations as to how the birth narratives of Matthew and Luke might be fit

together into a unified and harmonious narrative. Armed with such explanations one

need not worry about any apparent conflicts in the story but receive them as

being in symphony with one another.

JTR

Tuesday, May 23, 2023

Augustine, Harmony of the Evangelists.2.6-8: John the Baptist & the Two Herods

In this episode, we are looking at Book 2, chapter 6-8 where

Augustine discusses the appearance of John the Baptist in all four Gospels, explains

the mention of two Herods (Herod the Great King of the Jews and his son Herod

tetrarch of Galilee) in the Gospels, and Matthew’s mention of Archelaus.

2.6: On the position given to the preaching of John the

Baptist in all the four evangelists.

Augustine calls attention to the fact that all four Gospels describe

the ministry of John the Baptist. For Matthew and Luke, John’s public preaching

ministry begins after their respective birth narratives. Mark does not have the

birth narrative but starts in 1:1, “The beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ,

the Son of God,” and then proceeds to John’s ministry. Luke makes mention of

the political setting (Luke 3:1-2) before describing John’s ministry. John also

appears early in the prologue to the Fourth Gospel: “There was a man sent from

God, whose name was John” (John 1:6). The four Gospel accounts of John

the Baptist, according to Augustine, “are not at variance with one another.” The

differences in detail among the four Gospels do not demand the same detailed

analysis as required with the genealogies. He encourages his readers to apply the

same methodology he used to harmonize apparent differences in the genealogies

to other such passages in the Gospels.

2.7: Of the two Herods.

Augustine here draws a distinction between Herod the Great,

under whose reign Christ was born, and his son Herod the tetrarch of Galilee in

the event someone might be confused about the mention of Herod’s death in

Matthew 2:15, 19 (Herod the Great) and the mention of Herod the tetrarch ruling

in Galilee in Luke 3:1. His response indicates that this was apparently an area

where some critics of the Gospels had claimed a contradiction.

2.8: An explanation of the statement made by Matthew, to the

effect that Joseph was afraid to go with the infant Christ into Jerusalem on

account of Archelaus, yet was not afraid to go into Galilee, where Herod, that prince’s

brother, was tetrarch.

Augustine here anticipates another point at which the Gospel

readers might encounter confusion. Matthew 2:22 says that Joseph was fearful to

go to Judea when he heard Archelaus ruled there, but then he went to Galilee

where Herod ruled. Augustine explains, however, that Galilee was not ruled by

Archelaus but by Herod the tetrarch. He notes a time difference between when

Archelaus ruled (and was replaced by Pontius Pilate) and the time when the

family of Jesus settled in Nazareth.

Conclusion:

Augustine offers

a harmonious and unified account of John the Baptist across all four Gospels. He

is attentive to any perceived misunderstandings that might arise as to the mention

of historical figures like the two Herods and Archelaus. We also see again in

this section some textual differences between Augustine’s Old Latin text and

the traditional Greek text of the New Testament. For example, when citing Mark

1:2 Augustine reads, “As it is written in the prophet Isaiah”; whereas, the

traditional text reads, “As it is written in the prophets.”

JTR

Thursday, May 18, 2023

Augustine, Harmony of the Evangelists.2.5: Harmonizing the Infancy Narratives of Matthew and Luke

In this episode we are looking at Book 2, chapter 5 where

Augustine harmonizes the infancy narrative in Matthew 1—2 and that in Luke 1—2.

2.5: A statement of the manner in which Luke’s procedure is proved

to be in harmony with Matthew’s in those matters concerning the conception and

the infancy of the boyhood of Christ, which are omitted by the one and recorded

by the other.

Augustine argues that there is “no contradiction” between the

two evangelist in their respective infancy narratives. Luke sets forth in

detail what Matthew omitted. Both bear witness “that Mary conceived by the Holy

Ghost.” There is “no want of concord between them.”

Matthew and Luke both affirm that Jesus was born in

Bethlehem.

Each is also unique. Only Matthew has the visit of the magi.

Only Luke has the manger, the angel announcing Jesus’ birth to the shepherds,

the multitude of the heavenly host praising God, etc.

Augustine notes that a deserving inquiry can be raised as to

the precise timing of the events in both Matthew and Luke, and how they can be

harmonized with one another. He then provides a narrative in which he weaves Matthew

chapters 1-2 and Luke 1-2 into one unified account, in this order:

Matthew 1:18: Introduction

Luke 1:5-36: The

conception of John and Jesus

Matthew 1:18-25: Announcement

to Joseph

Luke 1:57—2:21: Luke’s

birth account (shepherds, angels)

Matthew 2:1-12: Matthew’s

account of birth (wise men)

Luke 2:22-39: The

visit to Jerusalem

Matthew 2:13-23: Flight

to Egypt and return to Nazareth

Luke 2:40-52: Family

Passover visit to Jerusalem when Jesus is twelve

Conclusion:

Augustine

provides his own merging of the two infancy narratives, perhaps in the same way

earlier writers like Tatian had attempted to blend the Gospels into one account

in his Diatessaron. Augustine is likely drawing on Old Latin translations

and his narrative provides several interesting textual variants. For example,

the angelic announcement in Luke 2:14 reads “and on earth peace to men of good

will [Hominibus bonae voluntatis],” diverging from the traditional text,

which would be rendered, “and on earth peace, good will toward men.” So, this

chapter is interesting not just for insights into harmonization but also

textual issues via the Old Latin version(s) cited.

JTR

Tuesday, May 09, 2023

Augustine, Harmony of the Evangelists.2.3-4: Genealogies

This is a series of readings from and notes and commentary upon

Augustine of Hippo’s Harmony of the Evangelists.

In this episode we are looking at Book 2, chapter 3-4 where

Augustine addresses both supposed conflicts between and among the genealogies

of Matthew 1 and Luke 3.

2.3: A statement of the reason why Matthew enumerates one

succession of ancestors for Christ, and Luke another.

Augustine begins by noting in particular a difference between

Matthew and Luke in the line between David and Joseph in the two genealogies. They

follow different directions with Matthew offering a series “beginning with

David and traveling downwards to Joseph,” and Luke, on the other hand, having “a

different succession, ”tracing it from Joseph upwards….” The main source of the

difference, however, is in the order between Joseph and David and the fact that

Joseph is listed as having two different fathers. Augustine explains that one

of these was Joseph’s natural father by whom he was physically begotten (Jacob,

in Matthew), and the other was his adopted father (Heli, in Luke). Both of

these lines led to David.

Augustine further notes that adoption was an ancient custom. Though

terms like “to beget” generally indicate natural fatherhood, Augustine notes

that natural terms can also be used metaphorically, so Christians can speak of

being begotten by God (e.g., cf. John 1:12-13: “to them he gave power to become

the sons of God”). Augustine thus concludes, “It would be no departure from the

truth, therefore, even had Luke said that Joseph was begotten by the person by

whom he was really adopted.” Nevertheless, he sees significance in the fact

that Matthew says “Jacob begat Joseph” (Matthew 1:16; indicating he was the

natural father) and Luke says, “Joseph, which was the son of Heli” (Luke 3:23;

indicating he was the adopted father of Joseph). Those unwilling to seek

harmonizing explanations of such texts “prefer contention to consideration.”

2.4: Of the reason why forty generations (not including

Christ Himself) are found in Matthew, although he divides them into three

successions of fourteen each.

Augustine begins by noting that consideration of this matter

requires a reader “of the greatest attention and carefulness.” Matthew who

stresses the kingly character of Christ lists forty names in his genealogy. The

number forty is of obvious spiritual significance in the Bible. Moses and

Elijah each fasted for forty days, as did Christ himself in his temptation. After

his resurrection, Christ also appeared to his disciples for forty days. He sees

numerological significance in the fact that forty is four time ten. There are

four directions (North, South, East, and West) and ten is the sum of the first

four numbers.

Matthew intentionally desires to list forty generations, but

he also suggests three successive eras (Abraham to David; David to Babylonian

exile; Babylonian exile to Christ). This would be fourteen generations each for

a total of forty-two, but Matthew, Augustine suggests, offers a double

enumeration of Jechonias, making it “a kind of corner” and excluding it from

the overall count, resulting then in the more spiritually significant number

forty.

Augustine suggests that Matthew’s genealogy stresses Christ

taking our sins upon himself, while Luke, who focuses on Christ as a Priest, stresses

“the abolition of our sins.” He sees significance in Matthew’s line from David

through Solomon by Bathsheba, acknowledging David’s sin, while Luke’s line

flows from David through Nathan, whom Augustine erroneously ties to the prophet

Nathan, by whose confrontation with David, God took away sin.

He also sees numerological significance in the fact that Luke’s

genealogy includes seventy-seven persons (counting Christ and God himself). He

sees the number seventy-seven as referring to “the purging of all sin.” Eleven

breaks the perfect number ten, and it was the number of curtains of haircloth

in the temple (Exodus 26:7). Seven is the number of days in the week. Seventy-seven

is the product of eleven times seven, and so it is “the sign of sin in its

totality.”

Conclusion:

The harmonization

of the genealogies has been a perennial issue in Gospel studies from the

earliest days of Christianity (see Eusebius’ citation of Africanus in his EH).

Augustine maintains the continuity and unity of both Gospel genealogies while

also noting the uniqueness of each individual Gospel account. In both

genealogies Augustine offers pre-critical insight into the intentional use of spiritually

significant numbers (forty in Matthew; seventy-seven in Luke) to heighten what

he sees as the theological perspectives and intentions of the Evangelists.

JTR

Addendum:

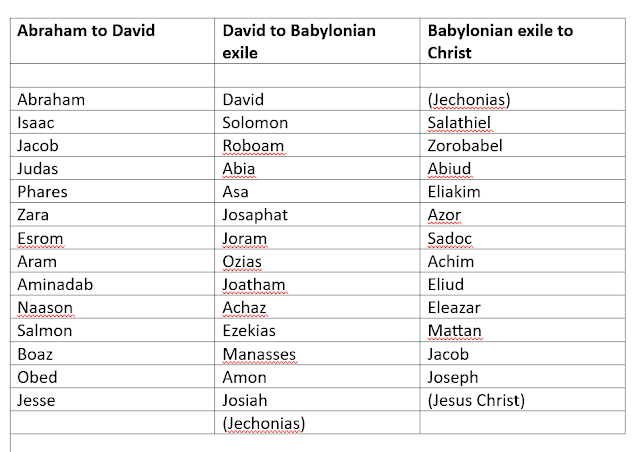

Here's a chart showing Augustine's breakdown of the genealogy in Matt 1:1-17 which yields 40 names according to his calculation. He excludes in his scheme Jechonias as "a kind of corner" and Jesus Christ as "the kingly president" over the whole.

Tuesday, March 14, 2023

Augustine of Hippo, Harmony of the Evangelists.2.1-2: The Son (as was supposed) of Joseph

Greetings, this is Jeff Riddle, Pastor of CRBC, Louisa,

Virginia and this is a series of readings from and notes and commentary upon

Augustine of Hippo’s Harmony of the Evangelists.

Note: We are resuming this series after a one-year break

(from March 2022).

We are in book 2 of 4. This second book is the longest in this work

with some 80 chapters. It covers the events recorded in the Gospel of Matthew,

with comparison to the other three Gospels, up to the Last Supper. These episodes will only be posted in audio (not video) format.

The Prologue:

Augustine begins by noting he intends to look into the four

accounts of Christ in the Gospels and show how they are consistent with one another.

2.1: A statement of the reason why the enumeration of the

ancestors of Christ was carried down to Joseph, while Christ was not born of

this man’s seed, but of the Virgin Mary.

This book begins with an analysis of the genealogy of the

Lord Jesus. Jesus is the Son of Man with respect to his true humanity. Augustine

notes also “the heavenly and eternal generation” of Christ as “the only

begotten Son of God. Matthew begins by tracing out the “human generation” in

the genealogy from Abraham to Joseph, husband of Mary.

He notes that Joseph and Mary were married, though she was a

virgin. They were an “illustrious recommendation” to “husbands and wives that

they may share affections of the mind, with “no connection between the sexes of

the body.” Augustine thus promotes his view that “carnal intercourse” is “to be

practiced with the purpose of the procreation of children only.” Joseph was not

the father of Jesus but had adopted him from another.

Augustine notes the statement from Luke 3:23 that Christ began

his public ministry at “about thirty years of age, being (as was supposed) the

son of Joseph.” Joseph could be called his “father” only if he was “truly the

husband of Mary, without the intercourse of the flesh, indeed, but in virtue of

the real union of marriage.”

2.2: An explanation of the sense in which Christ is the son of

David, although He was not begotten in the way of ordinary generation by Joseph

the son of David.

He begins by saying that even if Mary did not descend from

David by blood, we could say he descended from David by virtue of his adoption

by Joseph. Given, however, that Paul said, Christ was “of the seed of David

according to the flesh” (Rom 1:3), we know that Mary also descended directly

from David. Given her connection to Elisabeth, she also came from the priestly

line. Thus, Christ came “from the line of the kings, and from that of the

priests.”

Conclusion:

The Gospel

story of Jesus begins with his human genealogy and his virginal conception.

JTR

Thursday, March 31, 2022

Augustine: The Four Gospels Are United, Because They Were All Written By Christ

Here are some notes from Augustine’s Harmony of the Evangelists 1.35,

which I shared on twitter (@Riddle1689). As he concluded Book 1, Augustine returned to his

purpose for this book, namely, to defend the unity and harmony of the Four

Gospels against the pagan critics. One of their arguments was that Jesus left behind

no writings and that his disciples had distorted the account of his life and

teachings.

Why does Augustine say the four Gospels have essential unity and can be

harmonized?

Harmony 1.35: It is

because Christ "stands to all his disciples in the relation of the Head to

the members of his body."

Harmony 1.35:

"Therefore when those disciples [the evangelists] have written matters

which he declared and spake to them, it ought not by any means to be said he [Jesus]

has written nothing of himself; since the truth is, that his members have

accomplished only what they became acquainted with by the repeated statements

of the Head."

Harmony 1.35:

"For all that he [Jesus] was minded to give... he commanded to be written

by those disciples whom he used as if they were his own hands."

Harmony 1.35: When

one reads any of the four Gospels "he might look upon the actual hand of

the Lord himself... to see it engaged in the act of writing."

JTR

Monday, March 28, 2022

Augustine, Harmony of the Evangelists.1.33-35: "As if they were his own hands"

1.33: A statement in opposition to those who make the

complaint that the bliss of human life has been impaired by the entrance of

Christian times.

Augustine defends Christianity against critics who charge

that its rise has impaired “the bliss of human life.” He makes reference to the

fact that the triumph of Christianity has indeed resulted in the decline of

theaters, the closing of dens of vices, and the celebrations of some sports.

Only those of low character, however, would protest the diminishment of such things.

Christianity has not brought about the failure of “true prosperity” but rescued

society from sinking “into all that is base and hurtful.”

1.34: Epilogue to the preceding.

Nearing the end of Book 1, Augustine returns to his purpose for

writing this book. He wants to show that the Gospels can be harmonized. He adds

that the Gospels are sufficient, without there being any extant writings from

Jesus himself. The disciples did not give a false account of his life, and

Jesus was not a mere man albeit with exalted wisdom. The prophecies of the Old

Testament predicted that Jesus would forbid the worship of the pagan gods. His

disciples did not depart from his teaching.

1.35: Of the fact that the mystery of the Mediator was made

known to those who lived in ancient times by the agency of prophecy, as it is

now declared to us in the Gospel.

Augustine begins by noting that Christ himself is the wisdom

of God of which the prophets spoke. Drawing on Plato’s Timaeus, he notes a distinction

between things above (eternity and truth) and things below (things made and faith).

Christ is the Mediator between these two realms, and between God and man.

Christ is the center of faith (things made) and truth (things eternal). This

mystery was spoken about by the prophets. Christ now stands as head of the body.

There is no need to have anything written by Jesus, for when his disciples

wrote it was as though he himself was “engaged in the act of writing.” He used the evangelists, "as if they were his own hands."

Conclusion:

Book 1 is brought to a conclusion. Augustine responds with a final

apologetic thrust against pagan critics, defending Christianity against charges

of being “puritanical.” He reinforces the fact that his goal in this work is to

demonstrate that the Gospels can be harmonized and that they accurately

reflect the teaching of Jesus. Though we have no writings from Jesus himself,

the Gospels are sufficient to convey what Jesus taught.

JTR

Wednesday, March 23, 2022

Augustine, Harmony of the Evangelists.1.31-32: "The God of the whole earth" (Isaiah 54:5)

Notes:

1.31: The fulfillment of prophecies concerning Christ.

Augustine continues to stress the prophecies concerning Christ

from the Old Testament. He is critical of pagans who might outwardly applaud

Christ but deny that he taught that the pagan gods should be abandoned and the

images destroyed.

Much attention is given to the reading and exposition of the servant

song in Isaiah 52:13—54:5, including the statement in Isaiah 54:5 that the

Biblical God is “the God of the whole earth.” This servant song, sometimes

known as the Fifth Gospel, provided a classic prophetic passion prediction in

the eyes of early Christians. Augustine points out, of course, that the pagans

did not typically deny the passion of Christ, so much as his resurrection. He sees

in the flowering and triumph of the Christian movement in the Roman world, the

fulfillment of these prophesies, since the Christian God is, indeed, the God of

the whole world.

1.32: A statement in vindication of the doctrine of the

apostles as opposed to idolatry, in the words of the prophecies.

Augustine challenges pagans who deny the prophecies by saying

Christ used magical arts or that the disciples invented them. He notes how the

Christian movement has extended among all the Gentile nations, surpassing the

synagogue, and enlarging its tent. It has even extended beyond the bounds of

the Roman Empire to the “barbarous nations” (the Persians and Indians). The

church has overcome the age of persecution when she was covered with the blood

of the martyrs “like one clad in purple array.”

It is plain to even “the slowest and dullest minds” that the

Christian God is now “the God of the whole earth.” He challenges the pagans to bring

forward any of their prophecies or divinations that prove otherwise. He notes

that many pagans say their gods have deserted them, because they have offended

these gods. They fail to see the failure of their religion is due instead to

Christ’s triumph in fulfillment of prophecy.

Conclusion:

Augustine continues his apologetic against the pagan religions.

Though this is a work on the Gospels, he wants to make plain that the life of Christ,

including his passion, was a fulfillment of the Old Testament writings,

especially Isaiah. He sees the triumph of Christianity in the Roman Empire and even

beyond as a providential evidence of the truth of the Christian faith.

JTR

Tuesday, March 08, 2022

Tuesday, February 15, 2022

Augustine, Harmony of the Evangelists.1.26-27: Idolatry & Prophecy

Notes:

1.26: Of the fact that idolatry has been subverted by the

name of Christ, and by the faith of Christians, according to the prophets.

Augustine argues that the Christian stance against pagan

idolatry was not a new teaching but one that is found in the Old Testament prophets.

This Old Testament teaching has been preserved by the Jews, even though they

reject Christianity. “Thus,” says Augustine, “the enemy of our faith has been

made a witness to our truth.”

The “demolition” of the polytheistic pagan system has come

from the God of Israel himself. To prove his point Augustine cites the Shema

of Deuteronomy 6:4 and the second commandment against graven images (Exodus

20:4). He further notes that the Christian movement fulfills the promise to

Abraham in Genesis 12, that through him and his seed the nations would be blessed.

Christ’s virgin birth also fulfilled the prophecy of Isaiah 7:14. The God of

the Bible has ordained the overthrow of pagan “superstitions” through Christ.

1.27: An argument urging it upon the remnant of idolaters

that they should at length become servants of this true God, who everywhere is

subverting idols.

Augustine notes again that the teaching against idolatry is found

not only in the books of Christians (the NT) but also in those of the Jews (the

OT). He further asks those pagan who have suggested that the Christian God is

really Saturn, why, then, they do not worship him. Why also do they not accept

his teaching that no other gods are to be worshipped? Augustine also chides the

pagans for worshipping their gods in secret for fear that the Christians will

take their idols and break them to pieces. He closes by suggesting that the

triumph of Christianity over paganism is a fulfillment of Psalm 72:14 that all

nations would serve the God of Scripture.

Conclusion:

Augustine continues his relentless attack on paganism. Christian

teachings on this topic are not new, but they are found in the Old Testament

prophets. Augustine presumes that Christianity has, in fact, already triumphed

over pagan idolatry.

Tuesday, January 25, 2022

Augustine, Harmony of the Evangelists.1.24-25: Pagan Toleration & The Works of God

Notes:

1.24: Of the fact that those persons who, reject the God of Israel,

in consequence fail to worship all the gods; and, on the other hand, that those

who worship other gods, fail to worship Him.

Having discussed the fact that the pagans have confused the

God of the Bible with Saturn and Jupiter, Augustine returns to his primary apologetic

point, namely, that pagan continuation of the worship of the gods and rejection

of the worship of Christ is both inconsistent with the tolerant theology of

paganism (in which all gods are worshipped) and with Christian theology

(which dictates that only Christ should be worshipped). He also stresses that

the exclusive worship of Christ was “announced beforehand” through the OT

prophets in their denunciation of idolatry.

1.25: Of the fact that false gods do not forbid others to be

worshipped along with themselves. That the God of Israel is the true God, is

proved by His works, both in prophecy and in fulfillment.

Augustine continues his apologetic against paganism by noting

that none of gods, even if mightier and more virtuous than another god, ever

interdicts the worship of that other god. Jupiter, therefore, does not

interdict the worship of Saturn, and chaste Dianna does not interdict the worship

of the crude Priapus. The God of Israel, however, forbids the worship of any

other gods by images and rites. Thus, the Biblical God shows that the pagan

gods are “false and lying deities,” and he is “the one true and truthful God.”

The pagans have no right to reject the one true God, because God’s

works prove him to be true. Augustine surveys various events from the Bible to

illustrate these works. Rather than point to primordial history (the

translation of Enoch, the flood and Noah’s ark), he begins in Genesis 12 with the

call of Abraham and the promise to bless the nations through his seed (fulfilled

in the birth of Jesus to the virgin Mary). He traces the patriarchs Isaac and Jacob,

and deliverance under Moses. He notes that from Abraham eventually came Judah

(the son of Jacob), and from him the Seed (Jesus) to bless the nations. The

works of God are demonstrated in that now there was a generation of Christians willing

to break apart the idols of their fathers.

Conclusion:

Augustine uses the quality of toleration in the practice of pagan

religion as a tool against that religion. He points to its logical inconsistencies,

arguing that the Biblical concept of one true God is proven by that God’s

actions in history.

JTR

Monday, January 17, 2022

Augustine, Harmony of the Evangelists, 1.22-23: Saturn & Jupiter

This episode

is a continuation of this series after a fairly significant break of c. four months (the last

recorded episode was September 20, 2021). In his introduction to this work, S. F. D. Salmond described the Harmony

as one of Augustine’s “most toilsome” works. After some preliminary information

on the Gospels, much of Book 1 has to do with rather tedious Christian apologetics

against pagan polytheistic religion. Nevertheless, we will continue to persevere

in the series alongside the listener and trust we will be edified in the

process. From this point I am going to do the episodes in an audio-only format

on sermonaudio.com.

1.22: Of the opinion entertained by the Gentiles regarding

our God:

Augustine surveys pagan misunderstandings of the Christian

God. Some associate him with Saturn, and point to the worship of the Jews on

the sabbath (Saturn’s day-Saturday).

The famed Roman scholar Varro, however, associated the God of

the Jews with Jupiter (Greek: Zeus). In Roman mythology, Saturn was the father

of Jupiter. Saturn had eaten all his children at their birth, lest they usurp

him. Jupiter, however, was hidden by his mother and eventually attacked his

father, conquered and expelled him, and freed his divine siblings from Saturn’s

body. Jupiter then became the king of all gods.

Augustine argues that whether pagans think the God of the

Bible is Saturn or Jupiter they have a problem. If they think he is Saturn, how

can the reconcile the fact that Saturn never forbade the worship of other gods?

If they think he is Jupiter, they should remember that, according to Roman

mythology, even after Jupiter dethroned Saturn, he did not forbid worship of

Saturn.

1.23: Of the follies which the pagans have indulged in regarding

Jupiter and Saturn:

In this chapter Augustine pokes holes in the mythology and theology

of paganism. He notes that though popular pagan religion relies on the stories

of the gods as fables, the more sophisticated see deeper meaning. Their

interpretations, however, are not consistent. Some follow a platonic view and

see the Ether (God) as a spirit and not body. Others follow the Stoics and see its

as body (pantheism?).

He cites writers of the past like the Greek Euhemerus and the

Latin Cicero who suggested that the gods were originally men who moved from

heaven to earth, as they did with Romulus and the Caesars.

Nevertheless, Augustine notes that the pagans assert they

worship Jupiter (a vivifying spirit that fills the world) and not a dead man.

Saturn, they say, was also not a man but the equivalent of

the Greek God Chronos (representing time). Augustine offers the jibe

that by making this defense the pagans admit that one of their chief gods is literally

temporal (time).

He notes that the Platonic philosophers have countered the

Christians by arguing that Saturn comes from the names for fulness (satis)

and mind or intellect (nous), so Saturn is “fullness of intellect.” Jupiter

then comes from the “the supreme mind” and is the spirit that serves as “the

soul of the world.”

If this is the case, Augustine retorts, they should tear down

the images and capitol dedicated to Jupiter and erect them to Saturn. Instead,

Saturn is a deity typically maligned as evil by the pagans.

Conclusion:

Augustine continues to deconstruct the mythology and theology

of paganism, pointing to the rational inconsistencies of pagan intellectual

interpretations of the myths of Saturn and Jupiter. His ultimate point will be

to suggest that the God of Christianity is superior to the myths of paganism,

however one might try to interpret them.

Monday, September 27, 2021

Wednesday, September 22, 2021

Augustine, Harmony of the Evangelists.1.19-21: God worshipped alone, or not at all

1.19: The proof that God is the true God.

Augustine continues to ask why the pagan Romans refuse to

offer worship to the Biblical God in the manner in which he desires to be

worshipped. He adds: “For unless he is worshipped alone, He is really not

worshipped at all.” He suggests that even the pagans will admit that their

deities have show less power than the one true God.

1.20: Of the fact that nothing is discovered to have been

predicted by the prophets of the pagans in opposition to the God of the

Hebrews.

Augustine here declares that the prophets of the pagan Gods,

like those of Sibyl, never predicted that the God of the Hebrews would be

worshipped by men of all nations. He makes reference to the devils confessing

Christ during his performance of exorcisms, but notes, “their contention is

that they were invented by our party.” In contrast to the pagan prophets, he

calls attention to the Old Testament prophets who accurately predicted the

coming of Christ.

1.21: An argument for the exclusive worship of this God, who,

while He prohibits other deities from being worshipped, is not Himself

interdicted by other divinities from being worshipped.

Augustine poses a logical challenge to his pagan opponents,

based on two contradictory opinions:

First, their religion claim that all gods are to be

worshipped. Why then do they not worship the God of the Hebrews?

Second, the God of the Hebrews demands exclusive allegiance.

If they worship him aright, why then do they not put away the other gods?

He closes with this question: “Who is this God, who thus

harasses all the gods of the Gentiles, who thus betrays all their sacred rites,

who thus renders them extinct?”

Conclusion:

Augustine continues to press the superiority of the God of

the Bible to the pagan gods. He especially makes the point that whereas the

pagan gods did not demand exclusive allegiance, the God of the Hebrews was

intolerant and demanded the exclusive allegiance of his worshippers. He also

contrasts the pagan prophets to the Biblical prophets. In this work on the

Gospels, it is important for Augustine to note the religious clash between the

intolerant God of the Bible and the supposedly tolerant gods of paganism.

Saturday, September 11, 2021

Saturday, September 04, 2021

Augustine, Harmony of the Evangelists.1.12-14: The Romans and the Jews

1.12: Of the fact that the God of the Jews, after the subjugation

of that people, was still not accepted by the Romans, because His commandment

was that he alone should be worshipped, and images destroyed.

Augustine declares that the Jews were defeated by the Romans and

expelled from Jerusalem because of “the most heinous sin” of putting Christ to

death. He adds that the Romans did not embrace the God of the Hebrews, because

he demanded that he alone be worshipped and that images would not be permitted.

He further notes that the Romans could not claim any moral superiority as to

why God gave them victory over the Jews. They had no “piety and manners” to commend

them, and, in fact, their early history reveals that Rome was originally an asylum

for criminals and that Romulus committed fratricide in striking down his

brother Remus. He closes by stressing the sovereignty of God, who acts as he

pleases “according to the fore-ordained order of the ages.”

1.13: Of the question why God suffered the Jews to be reduced

to subjection.

Why did God permit the Jews to be defeated by the Romans? For

Augustine the answer is simple: It came about, because in their “impious fury”

they put Christ to death.

1.14: Of the fact that the God of the Hebrews, although the

people were conquered, proved Himself to be unconquered, by overthrowing their idols,

and by turning all the Gentiles to His own service.

Augustine points out the fact that Christ is now being preached

and worshipped across the Roman Empire. This fulfills the promise made to

Abraham that all nations would be blessed through his seed (Gen 12). God took kingdom

and priesthood from the Jews, because Christ is the true King and Priest. This

was announced by the prophets (without the use of magical arts). Christ could

not have written books promoting magical arts, because his doctrine is so vehemently

opposed to it.

Thursday, August 26, 2021

Augustine, Harmony of the Evangelists.1.8-11: Jesus was not a magician

1.8: Of the question why, if Christ is believed to have been

the wisest of men on the testimony of common narrative report, He should not be

believed to be God on the testimony of the superior report of preaching.

Augustine continues to respond to those who reject the

authenticity and historical reliability of the Gospels in their presentation of

Jesus. He notes that these skeptics hypocritically affirm that Christ was the

wisest of men, based on various reports about his life, but then reject the

Gospels, which are based on eyewitness reports from his closest followers. The

Gospels present Jesus as the only begotten Son, as God himself, and as the creator

of all things. He then counter-punches by asking why the pagan deities should

be considered “proper objects of reverence” if they are ridiculed in popular

theatrical productions. He challenges those who say they have books written by

Jesus which support their view to produced them.

1.9: Of certain persons who pretend that Christ wrote books

on the art of magic:

Here Augustine attacks those who make the false claims that

they have books written by Jesus on magic, which he used to produce his

miracles. If they have these books, he challenges such persons to use these

books to do the miracles Jesus did.

1.10: Of some men who are mad enough to suppose that the

books were inscribed with the names of Peter and Paul:

The attack continues, as Augustine points out that some of

the spurious “magic” books have nonsensical dedications to Peter and Paul.

These claims show their “deceitful audacity” and ignorance, making them a laughingstock.

It would be total folly to suggest that Jesus wrote anything to Paul, who did

not become a follower of Jesus during his earthly ministry but only after his

resurrection. Augustine chides such men for getting their information about

Christ and the apostles “not in the holy writings, but on painted walls.” He

notes that such spurious views likely developed in Rome where Peter and Paul

were martyred on the same day. These men had then misunderstood paintings which

depicted Jesus with Peter and Paul.

1.11: In opposition to those who foolishly imagine that Christ

converted the people to Himself by magical arts:

Augustine here offers another challenge to those who claim

Jesus did his miracles by magic. If this is so, how do they explain the fact

that the prophets wrote about him. If he used magic to influence them, then he

was “a magician before He was born.”

Conclusion:

Augustine here continues his defense of the canonical

Gospels, especially against popular pagan traditions, which suggested that

Jesus had been a magician and used magic to manipulate circumstances and

perform miracles. He shows that books presenting this view which claimed to be

written by Jesus are spurious. He is especially critical of those who have

received a distorted view of Jesus based on visual art (paintings) rather on

the written Scriptures. His purpose, again, is to show the superiority of the

canonical Gospels as sources for the life of Jesus.

JTR

Wednesday, August 11, 2021

Augustine, Harmony of the Evangelists.1.6-7: Why didn't Jesus write anything?

1.6: Of the four living creatures in the Apocalypse, which

have been taken by some in one application, and by others in another, as apt

figures of the four evangelists.

Augustine discusses here the so-called “tetramorph,” a

development in early Christian literature and art, in which the four

Evangelists are depicted as the four living creatures in Revelation 4:6-7 (cf.

Ezekiel 1:10).

Most early interpreters suggested the winged man to represent

Matthew, the winged lion to represent Mark, the winged ox to represent Luke,

and the eagle to represent John.

Augustine, however, reverses the first two by suggesting that

Matthew should be the winged lion, given his royal emphasis on Jesus as king,

and Mark, as the winged man, since he specifically describes Christ neither as

king or priest.

He also mentions that some associated the man to Matthew, the

eagle to Mark, and the lion to John.

He suggests the ox is right for Luke given his emphasis on

Jesus as priest, and the eagle for John, since “he soars like an eagle” in his

high Christology.

1.7 A statement of Augustine’s reason for undertaking this

work on the harmony of the evangelists, and an example of the method in which

he meets those who allege that Christ wrote nothing Himself, and that His

disciples made an unwarranted affirmation in proclaiming Him to be God.

Augustine begins this chapter by describing the Gospels as

“chariots” in which Christ is “borne throughout the earth and brings the

peoples under His easy yoke, and his light burden.” Calvin will later borrow

this image in his Harmony of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. Augustine also notes the

calumnious attacks on the Gospels by those who want to keep men from the faith.

Thus, he sets out in particular to show that the Gospels “do not stand in any antagonism to each other.”

He also addresses the criticism raised by some that Jesus

himself wrote nothing, but that we learn of his life and teaching only through

the writings of his disciples, who exaggerated their master. Such men say Jesus

was the wisest of men, but they deny that he is to be worshipped as God.

Augustine responds by pointing out that some of the most

admired pagan philosophers left behind no writings, like Pythagoras and

Socrates, but were written about by his disciples. If they accept their records

of the philosophers, then why not accept the Gospel accounts of Jesus?

Conclusion:

In his discussion of the tetramorph, Augustine continues to

discuss what makes each Gospel distinctive. He also engaged here in

apologetics, defending the harmony of the Gospels and their historical

reliability, even though they contain nothing written by Jesus himself.

_-_James_Tissot.jpg)

_-_Isaiah_-_P297_-_The_Wallace_Collection.jpg)